{Shikoku Hachijūhachikasho Meguri}

--WALKING--

--PILGRIM'S CLOTHING--

--WALKING--

--PILGRIM'S CLOTHING--

Pilgrim's Clothing

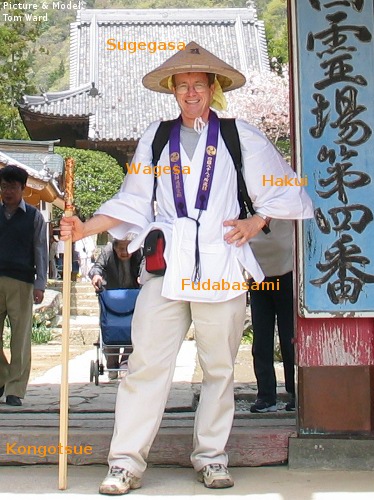

First off, the traditional dress. While you won't have to dress like the henro from Shinnen's Shikoku Henro Michi Shirube to be outfitted correctly, a henro should wear the following:

First off, the traditional dress. While you won't have to dress like the henro from Shinnen's Shikoku Henro Michi Shirube to be outfitted correctly, a henro should wear the following:

There will be 5 lines of kanji written on the hat: "dogyo ninin" will be one line, then four others that make up a poem, of sorts. In addition there will be one solitary sanskrit character, the character for Kōbō Daishi. When you wear the hat, always wear it with this one sanskrit character facing forward.

Traditionally, the kongōtsue represents Kōbō Daishi, your constant companion during your walk. It would also serve as a henro's gravestone and have been placed at the head of the grave of any henro who died and was buried beside the trail. Since it represents Kōbō Daishi, you must respect it and take good care of it. In the "old days," when you stop for the night, whether at an inn or somewhere you intended to camp, the first thing you did was wash the bottom of the stick (symbolizing washing the Daishi's feet). Only after doing that would you can take care of your needs. If you stayed in an inn, the kongōtsue would be kept in the tokonoma (if there is one) of your room overnight.

Today, however, you leave your kongōtsue in a holder which looks like a large vase, inside the lodging and right next to the entrance. It is very, very rare to take it to your room. There have only been a few times over the years when the owner of the inn has given me a bucket of water and told me it was to wash the bottom of the stick. A couple of times during each walk the owner herself will actually take it from me and wash it herself. In general, though, this custom is slowly disappearing.

At least that's the official story. The editor of the guidebook Shikoku Japan 88 Route Guide, however, sent me the following additional information:

People are now forgetting that this idea of not letting your kongōtsue touch the ground while crossing a bridge was originally disseminated in order to protect the bridges. Long ago, there were earthen bridges, wood plank bridges, log bridges, stone bridges, and even pontoon bridges, but earthen bridges were by far the most common. The strength of a bridge's surface was significantly increased by placing logs along it and then covering that with hard packed soil, but it was weakened by the continuous poking by traveller's walking sticks. Henro young and old, tend to walk in lines, one in front of another, and when line after line of henro cross over the bridges, all stabbing the surface of the bridge with their kongōtsue, the surface of the bridge would be seriously damaged. Someone in the past might have borrowed the story about the Daishi's need for sleep in order to protect the bridges.

I'm still using the same bag i bought back in '99 when i knew nothing about the henro and i have always called it a fudabasami. Looking at a catalog as i type this, though, i see that what i have is a zutabukuro. It's a smaller white cotton bag (half the size of what Tom has in the picture above), with the long neck strap but no internal pockets or compartments, and with velcro holding a flap closed over the top so nothing falls out. On the front of that flap are the words Dōgyō Ninin and the Sanskrit character (bonji or shushi) associated with Kōbō Daishi. I prefer my zutabukuro because it is noticably smaller than the typical fudabasami — just big enough for my nōkyōchō, the map book, candles, incense, osamefuda, and whatever candy i receive as settai from time to time. There is no extra room, and yes, stuff does get crumpled, broken, etc. from time to time.

I'm still using the same bag i bought back in '99 when i knew nothing about the henro and i have always called it a fudabasami. Looking at a catalog as i type this, though, i see that what i have is a zutabukuro. It's a smaller white cotton bag (half the size of what Tom has in the picture above), with the long neck strap but no internal pockets or compartments, and with velcro holding a flap closed over the top so nothing falls out. On the front of that flap are the words Dōgyō Ninin and the Sanskrit character (bonji or shushi) associated with Kōbō Daishi. I prefer my zutabukuro because it is noticably smaller than the typical fudabasami — just big enough for my nōkyōchō, the map book, candles, incense, osamefuda, and whatever candy i receive as settai from time to time. There is no extra room, and yes, stuff does get crumpled, broken, etc. from time to time.

Of course, there are other items that a completely outfitted henro can carry, but anything in addition to what is listed above seems to be extra. These "extra" could include: a buddhist rosary (juzu or nenju) for use at the temples (Some people carry it wrapped around one of their wrists throughout the day); tekō, cotton covers worn over the back of the hands; kyahan, cotton gaiters to cover your ankles and the top of your boots; and even possibly jikatabi, white, cotton socks with a pocket for each toe, worn when you also wear waraji, straw sandals, instead of boots.

Let me stress, though, that you don't need to carry or wear any of the above to be a henro. What i have listed above is simply what has come down through history as the traditional dress. A i mentioned on the previous page, one of the nice things about this pilgrimage is that there is nothing that is considered right or wrong. Anything you wear can be considered more or less traditional, but not wrong. I wore a light colored hat, but not the henro hat. In 1999 i didn't carry the fuda-basami as i kept everything in my back pack, although starting in 2004 i did carry one. In 1999 i didn't wear a bell on my belt, but i did starting in 2005. When i was on the trail i saw several henro in non-traditional garb, including some in blue jeans.

Notes:

Just to offer my opinion, let me say that i think all henro (yes, i mean ALL) should carry a walking stick and wear the white hakui, even if you wear no other henro related clothing. These two items single you out and let everyone know that you are a walking henro. Whether you believe me or not, this will affect your pilgrimage as just by having these two items, people will interact with you in a much different manner than if you don't have them. When people see them, they see a walking henro, as opposed to a foreign tourist, which they may or may not interact with. These items are fairly cheap — buy them. You won't regret it.

While Japanese adults still do not wear shorts in public (typically), more and more shorts are appearing on the henro trail. I see them regularly now; beginning in about the spring of 2016. But the catch is, they always wear ankle length tights underneath them. So, while you will see shorts on the trail now, you still will not see bare legs.